As the invasion phase of the Russo-Ukrainian war enters its fourth year, there is a growing popular and political demand to find some way to resolve the conflict in all countries directly or indirectly involved. With the election and inauguration of US president Trump it seems more likely than before that some sort of ceasefire will be reached, and less likely than before that such a ceasefire will last.

American president Donald John Trump and Russian president Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin meeting in Finland, July of 2018. Picture via the New York Times

Trump’s recent diplomatic moves have weakened Ukraine’s position significantly, without giving Ukraine or Ukraine’s European backers any incentive to enter negotiations. What’s more, he has created a rift in western relations and cohesion that might end up upending the current US-led global order. The US abandoning a democratic ally in a defensive war is not a good look, and is not a plan that conforms with American strategic interests in the long term.

This article will explore the future of the Russo-Ukrainian war, and where negotiations may lead on the fields of NATO membership, security guarantees, territorial concessions and EU membership. I will also in the end go into what the consequences of such a deal would be, and whether it is possible for the war to go on instead.

Leverage

If Russia and Ukraine are to enter peace talks, they do it from radically different positions. Understanding the diplomatic and military leverage the two sides have is crucial for understanding what demands each side can make in any hypothetical negotiations.

Russia is the bigger country of the two, in geographic, demographic and economic terms. Russia is also the aggressive part in the conflict, and the one that is currently, albeit slowly, on the offensive. That offensive comes at a cost, however. Russia is also the side that loses the largest number of soldiers every month, and the side that loses the largest amount of heavy equipment.

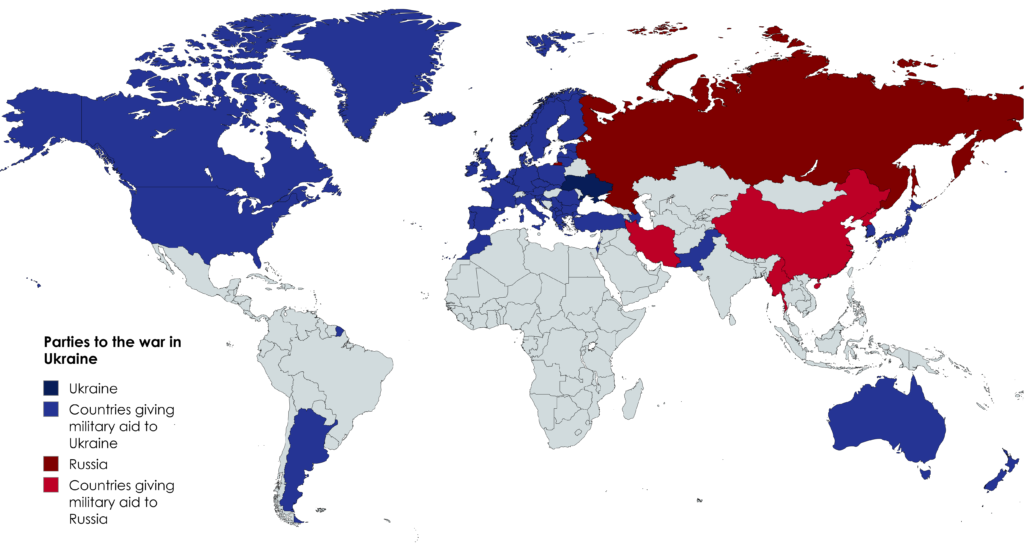

Ukraine, on the other hand, is on the defensive with the diplomatic support of much of the world. The support in military equipment Ukraine receives from abroad is far more than Russia does, both in how many countries are sending and how much it amounts to.

A map overview of countries providing or having provided military aid during the war, military aid being either weapons, ammunition or other equipment. Support from each country varies. Belarus, despite having allowed Russian troops to pass through its territory at the start of the war, has not given any known direct aid to Russia.

Russia is the side that appears to hold the most cards in a negotiation now, but it’s not clear that will last. The advantage that the Russian army has pushed has been their superior numbers, and importantly their superior access to artillery ammunition. In 2024 the US and EU combined produced an estimated 1 million artillery shells for Ukraine, which was trumped by the Russian production that same year of 3 million artillery shells. In 2025 the EU is expected to produce 2 million artillery shells alone, evening the odds.

Russia had the advantage in heavy weaponry in 2024, and with that the Russian army managed to capture a total area of around 4000 square kilometers. Considering the Russian army captured an area of almost 120 000 square kilometers during the first two months of the invasion, the speed is not exactly groundbreaking. If the Russian advantage in arms disappears, which it very well might even without US aid for Ukraine, the front will stall entirely. If US aid resumes, Ukraine might start pushing Russia back again.

NATO

A key Russian demand prior to the full-scale invasion was that they would be guaranteed that Ukraine would not be made a member of NATO. Certain western scholars like Mearsheimer have argued that preventing Ukrainian NATO membership is Russia’s prime or even only goal in invading Ukraine. The demand remains central in Russian rhetoric around a possible peace deal.

If Russia’s only goal was to prevent Ukrainian accession to NATO, they would have already achieved that goal. A membership requirement in NATO is that new member states have to have their territorial issues resolved before joining. While it is not a formal rule, all NATO countries have agreed on this principle, and membership requires the consent of all current members.

Ukraine had no territorial issues before the Russian annexation of Crimea and backing of the rebels in the Donbas in 2014. From then on, Ukraine was not a viable option for NATO enlargement, and Russia had essentially given itself veto rights on Ukrainian NATO membership using very limited military means. The Russian aggression meant Ukraine and NATO would be more closely linked than before, but full NATO membership was off the table.

Russian actions do not show a fear of aggressive military action from NATO. If Putin’s regime was as paranoid of a western attack as they present themselves as being, the Russian army would not strip forces away from its borders with neighboring NATO countries. If Russia was paranoid of NATO expansion they would likely fortify the Finnish border, not draw troops away from it. In 2018, years before the invasion started, the main force of the Russian army was already stationed in the surroundings of Ukraine, not any NATO member state.

Russian fears of Ukrainian NATO membership specifically is more likely motivated by a fear of letting Ukraine permanently leave the Russian sphere. Ukrainian NATO membership would mean that Russia will not be Ukraine’s main ally for the foreseeable future. Ukraine joining NATO does not mean that Russia would have to fear a massive invasion from the west, but it would mean another permanent loss of influence.

UN peacekeepers, here on camelback in Eritrea

Ukraine’s NATO application was submitted half a year after the start of the invasion, not before. If anything, the war has made Ukrainian NATO membership more likely. Russia is also likely to eventually allow Ukrainian membership as a bargaining tool. The war has turned Ukraine so thoroughly against Russia that the point about Russian influence is moot. Ukraine will not willingly rejoin the Russian sphere again for a long time.

On Ukraine’s end, a settlement of the war without some kind of security guarantee from the West is not an option. Russia’s larger economy and population will let them rearm faster than Ukraine if only a ceasefire is reached, and without any security guarantees there is nothing that is stopping Russia from invading again. Such a security guarantee does not need to be a full NATO membership, however. A treaty of mutual defense with NATO or even just a handful of powerful NATO countries would have the same effect.

Multiple NATO countries have stated their willingness to provide peacekeepers to the frontline to act as a guarantee that the war does not start up again in the event of a ceasefire. Lavrov has ruled out the possibility of Russia accepting this, but he has also ruled out every other concession Russia might make. If security guarantees and peacekeepers means Ukraine will accept a ceasefire, it is likely Russia will accept that.

Territories

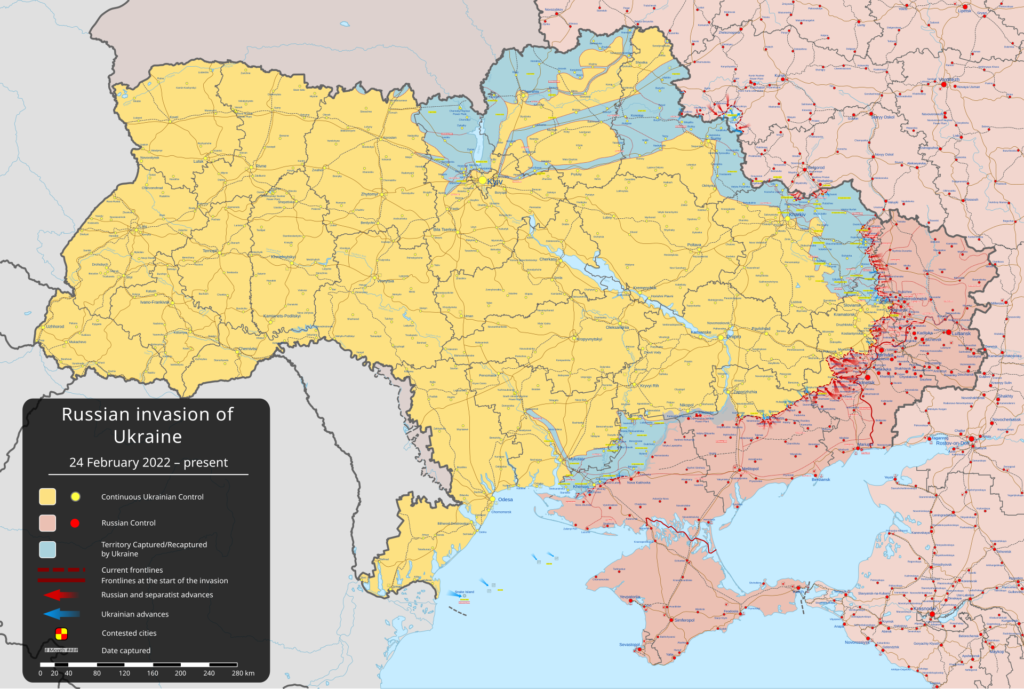

Russia occupies almost a fifth of Ukrainian land, mainly in the south and east. Russian forces occupy the entirety of Crimea, and most of the four oblasts Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson. The regional capitals of Donetsk and Luhansk are in the Russian controlled regions, while Kherson and Zaporizhzhia remain in Ukrainian control. On the other hand, Ukraine controls a region within the Kursk oblast of Russia, large enough to have to be addressed in negotiations.

A map of Russian and Ukrainian control of territory. Picture from Wikimedia commons.

Ukraine wants Russian forces out of all of Ukraine, while Russia has demanded that Ukraine should leave the parts of the four oblasts that Russia is still not occupying. The territorial contradiction is obvious, physical, and hard to compromise over. Land is held by one side or the other, and there is no way to make Crimea both Russian and Ukrainian at the level of trust we see today.

It is somewhat unclear whether Russia’s goal from the start was to specifically annex the regions they did. The push on Kyiv in the opening weeks of the war combined with Putin’s claims of “denazification” seems to imply that the goal was initially to force a regime change in Ukraine, in which case annexing parts of the new puppet state would not be necessary. The fact that it took Russia seven months to annex the oblasts while it had taken days to do it in Crimea years before indicates that the annexation of territories may not have been the initial plan.

Regardless of whether Russia initially planned to annex the oblasts, the decision to annex them makes it very difficult for Putin to now backpedal and cede some part of them away, as Russia legally considers them Russian territory just as much as Kursk oblast is. Trading lands in Kursk for lands elsewhere would be an admission that the newly annexed regions are “less Russian” than the rest of Russia, which would clash with the official stance of the government.

The Kursk occupation zone is, however, very likely to be traded away for some sort of concession. Ukraine has no legal claim to the Kursk region, and the war is not their war of conquest. While Russia does not consider Kursk any more Russian than Kherson, the rest of the world does, and it would be an embarrassment for a great power to have a portion of their land occupied.

Ukrainian president Zelensky has opened up for the possibility to let Russia temporarily keep control of the occupied lands, if Ukrainian security can be guaranteed and the occupation is not recognized by any other state. This would give the newly annexed oblasts essentially the same status as Crimea, which has remained annexed and unrecognized since 2014.

Russia’s demand for Ukraine to leave the remainder of the four oblasts is inconceivable for Ukraine to accept, and is likely a negotiating tactic so that Russia has something to give. If Russia maintains that as a demand, the negotiations will be short lived. If the US agrees to a peace deal and Ukraine does not, the war is not over.

Keeping the occupied land is not a major win for Russia. Half the pre-war population has left, and much of the region’s valuable infrastructure has been destroyed during the war. Mariupol, which was a major industrial hub and the largest port in the Azov sea, was devastated during the Russian capture of the city. If Russia wants to get economic value out of the region, they will also have to pay for its rebuilding.

While keeping the land is not a major win for Russia, it is unquestionably a loss for Ukraine. Over three million people will be made Russian citizens, while the three million who fled the occupied regions during the Russian advance will be unable to return to their homes. Additionally, the industry that Russia has taken over and destroyed was a part of the Ukrainian economy, and that loss will be felt more in Ukraine than the inability to exploit it will be felt in Russia.

The European Union

The root of the contemporary conflict, before Crimea and before the Donbas war, was the Euromaidan revolution in Ukraine. The beginning of that revolution was spurred on by then-president of Ukraine, Viktor Yanukovych, cancelling a trade deal with the EU. Anger over that decision spiraled into a revolution that saw Yanukovych flee to Russia, Russia annexing Crimea, and the hostile Russo-Ukrainian relationship lasting to this day.

Yanukovych cancelling his deal with the EU was likely due in part to Russian pressure, and partially from the EU placing demands of democratizing reform on his government. For the Ukrainian people, the EU deal had been a source of hope, and would have provided economic growth for the country.

When the protests kicked off, the goals of the protesters were augmented to also want rule of law, less corruption and more democratic governance. To Ukraine, the difference between Europe and Russia is also the difference between democracy and oppression, it is the difference between openness and corruption, and the difference between a fair standard of living and poverty.

Eventual EU membership for Ukraine does not require solving the territorial issues, as Cyprus has proven the EU has no such rule. EU membership is also not a red line for Russia, as opposed to NATO membership, something which has been made clear by a spokesperson for the Russian government. Membership for Ukraine still requires the country to finish reforms on corruption and end martial law, but beyond that Ukrainian accession to the EU will be possible as long as all current members approve.

EU membership would likely help Ukraine on its post-war economic recovery, but it would also serve as a security guarantee. Article 42 of the Treaty of the European Union contains a mutual defense clause, which means that the EU in theory when challenged should serve as a defensive alliance. The EU as a security alliance is largely untested, but if the security guarantees for Ukraine are given by the EU instead of by NATO it would force the organization to take a more active role.

As it stands, the goal in Ukrainian foreign policy that will most likely become reality is Ukrainian EU membership. EU membership is not, however, something that comes as part of a ceasefire or peace deal with Russia, but is rather achieved through the EU’s standard membership process. Other countries, likely European, will still have to act as guarantors of Ukrainian security in the interim between a ceasefire and full Ukrainian membership.

Conclusion

If a ceasefire is to happen in the coming weeks or months, it will probably include little territorial change, while entailing security guarantees for Ukraine. If Russia keeps demanding more land, or keeps blocking any NATO country from deploying peacekeepers to Ukraine, the ceasefire will be a ways off. Such a ceasefire, which would not resolve the legal status of southeastern Ukraine, would doubtfully result in a peace deal until another large change happened.

A ceasefire where Russia keeps southeastern Ukraine would not be satisfactory for any side. Ukraine would have lost the war, and Russia would not have properly won it. While the Russian people has suffered from the war, the Russian government will still be capable of pointing to the land and claiming a victory.

A ceasefire deal now would be more worrying in its implications for international law. Russia would then have proven that it is still possible to use military might to force a fait accompli, and that they are capable of breaking the will of the US in enforcing international law and its own interests.

This is an opinion piece. Sources given on request

Leave a Reply