Ever since the end of the French colonial empire in the 1950s and 1960s, France has remained an important partner to most of its former African colonies. The system of military, political and economic cooperation of France in Central and Western Africa has been dubbed the “Françafrique”. French influence is maintained through the use of the CFA Franc, by Francophile and often French-educated elites staying in power, and, when needed, by the use of military force against those elites’ opponents. This is the second article on the Françafrique and its possible end, covering the French military commitments in and later withdrawals from Africa.

After decades of limited direct military intervention in Africa, the French military began a gradual buildup of its commitment in Central and West Africa. Year by year the French would see a greater number of soldiers stationed at a greater number of bases in a greater number of countries, before efforts peaked in the late 2010s. Then, after a few years of hovering around that peak, nearly all French forces in Africa were withdrawn in the 2020s.

This article will paint a picture of the scale and importance of the interventions and subsequent withdrawals, and ask a few questions. Why was a French military withdrawal desired by local armies and governments actively cooperating with them? To what extent has France had a choice in the matter of withdrawal? What will the end of French military commitment in Africa mean, and can we be sure they won’t return? Is this the end of the Françafrique?

The interventions

In 2012, the president of France, François Hollande, proudly declared the end of the term “Françafrique” while holding a speech in Senegal.[1] He was carrying out a diplomatic tour of former French colonies in the year of his election, and wanted to signal that a socialist president would mark a departure in French policy towards Africa. Before leaving, he promised French journalists that, while he would aid the Malian government in their war against Al-Qaida, he would not send any French soldiers to participate in the war directly.[2]

French president Francois Hollande and Senegalese president Macky Sall inspecting Senegalese troops in 2012. (AP photo)

Two months after Hollande’s pledge, in January of 2013, French forces would enter Mali in force in Operation Serval. The operation was a rapid success, and within two weeks, Gao, the largest city in Northern Mali, had been recaptured by the French and Malian forces. The deployment of 4000 French soldiers had been effective, but it bound Hollande’s government to a war that it had not planned to participate in. French forces would remain in Mali for nine years, and leave without a final victory.

Two Serval cats, the species which the operation was named after. (Wikimedia commons)

Operation Serval would in 2014 be transformed into Operation Barkhane, a long-term stabilization mission in the wider Sahel. Together with Operation Sangaris in the Central African Republic’s civil war, France would remain committed and deployed in two wars and nine countries, all of them former colonies. The scope of the combined interventions in the 2010s marks the highest degree of French military activity in Africa since decolonization.

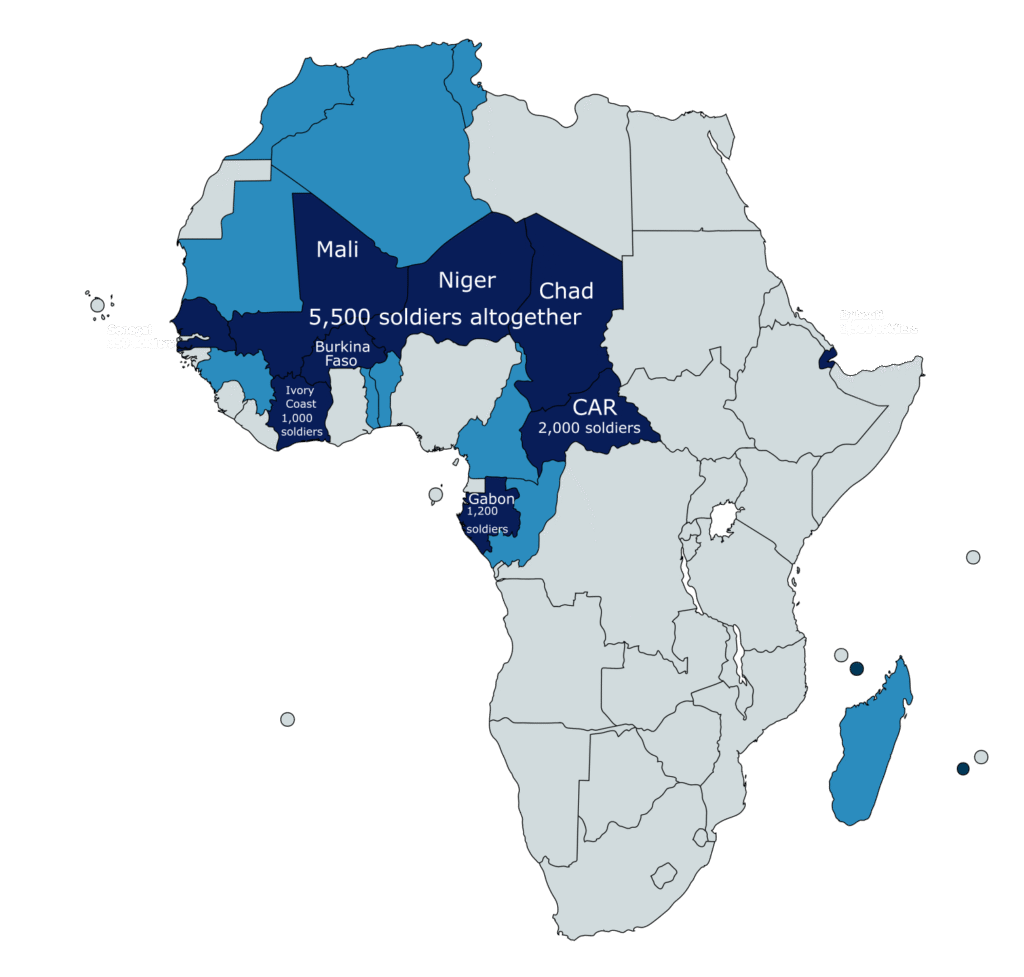

Operative French forces were deployed in Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Chad as part of Operation Barkhane, and in the CAR as part of Sangaris. This came in addition to permanent French forces already being stationed in Senegal, the Ivory Coast, Gabon and Djibouti. At its peak in the late 2010s, more than 10 000 French soldiers were deployed in former French colonies in Africa at the same time.

Countries with a French deployment of forces in the 2010s is marked in darker blue, while former French colonies without a French military presence are marked in a lighter blue. The numbers given are how many troops were deployed at its peak through the decade.

The importance of the list of countries and the number of soldiers is what it says about the scale of French involvement in the context of French capacity and in comparison to other interventionist powers. For one, a deployment of over 10 000 troops is equivalent to about 10% of the size of the French army, and is slightly larger than the army of France’s neighbor Belgium.

The more important implication of the number of countries soldiers in the French intervention is that it makes the total French deployment in Africa the largest of any non-African country in the 2010s, beating out the US, which in 2018 had 7200 military and civilian personnel stationed in Africa.[3] American and EU forces took supporting roles in France’s war effort, making France, for a few years, the de facto military leader in African operations carried out by the West.

The deployment of military force to stop rebels at the request of another government is, in itself, hardly neocolonial. François Hollande may be excused for turning around and deciding that, after all, hindering Al Qaida in their ongoing conquest of the Malian state was more important than sticking to his word. As with many aspects of France’s complicated African political stance, the new interventions of the 2010s were not malicious, but they add to a larger picture of France’s great power politicking.

The deployment of French forces to the Sahel and Central Africa served to protect vested French interests. Every late French intervention was done in the CFA Franc zone (which was discussed in my last article). The interventionism has indeed been primarily directed at preserving the power of African governments, but not as part of a wide humanitarian mission. No government outside of the French sphere of influence has received their support.

Sources

[1] https://www.france24.com/en/20121012-hollande-senegal-speech-new-story-france-africa-end-franceafrique-dakar-sarkozy

[2] https://www.france24.com/en/20121011-france24-exclusive-interview-france-president-francois-hollande-africa-dr-congo

[3] https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Waldhauser_03-13-18.pdf

The tide turns

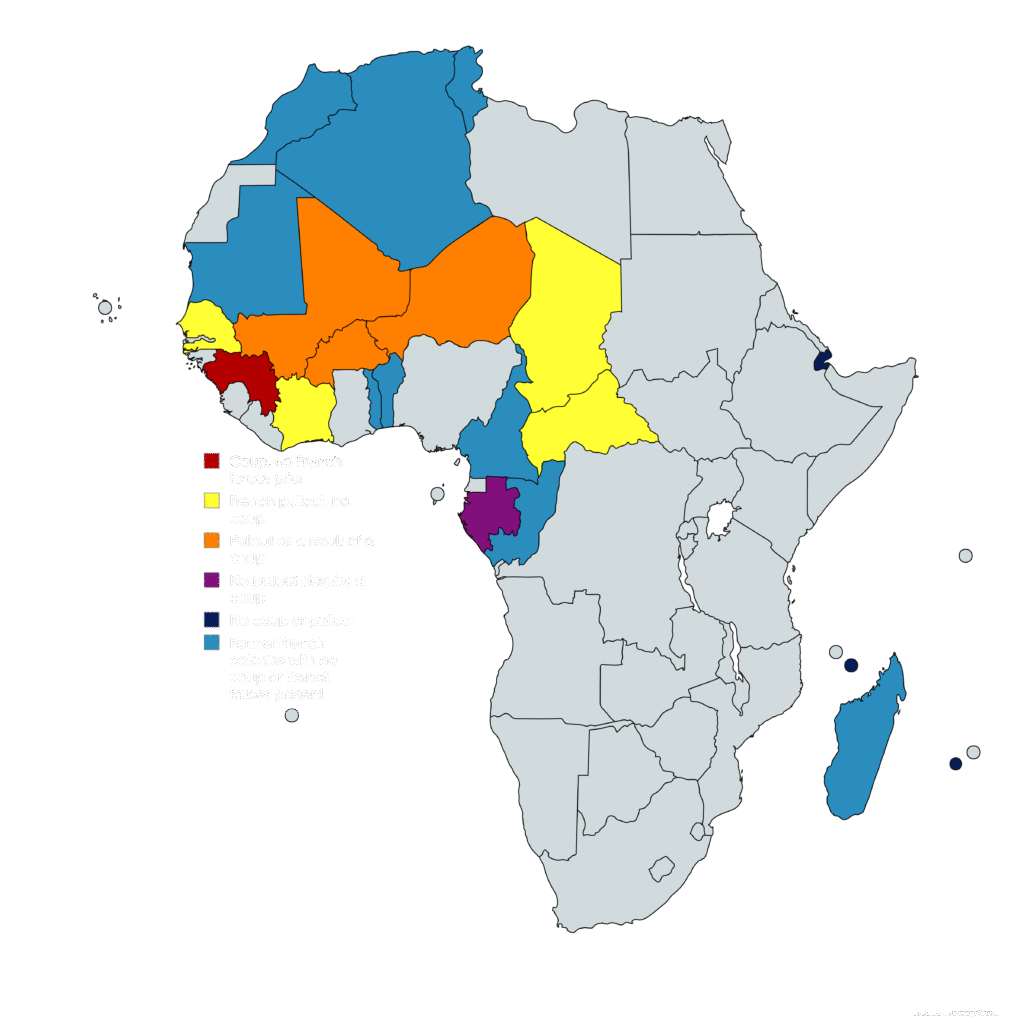

The early 2020s have been marked by a high number of coups in Africa, with a particularly high number of Francophone countries seeing a transition to military rule. Following the wave of coups came a series of French military withdrawals and expulsions from Africa. Most discussions of the French withdrawal end here, with the coups leading to the French leaving and being replaced with the Russian Wagner group. This mainstream version of events is somewhat simplified, as not all French withdrawals have been a result of coups, not all coups have led to French withdrawals, and Wagner only serves as a partial replacement for the French forces in a few countries.

Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso are the three countries that really fit the narrative of the French withdrawal being a result of a series of Russophile coups. All three countries were couped by their armies with only a year between each coup, expelled the French shortly thereafter, and invited Wagner to help their war effort. The three of them have formed into a new alliance, the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), breaking with both their old African and European allies in the process.

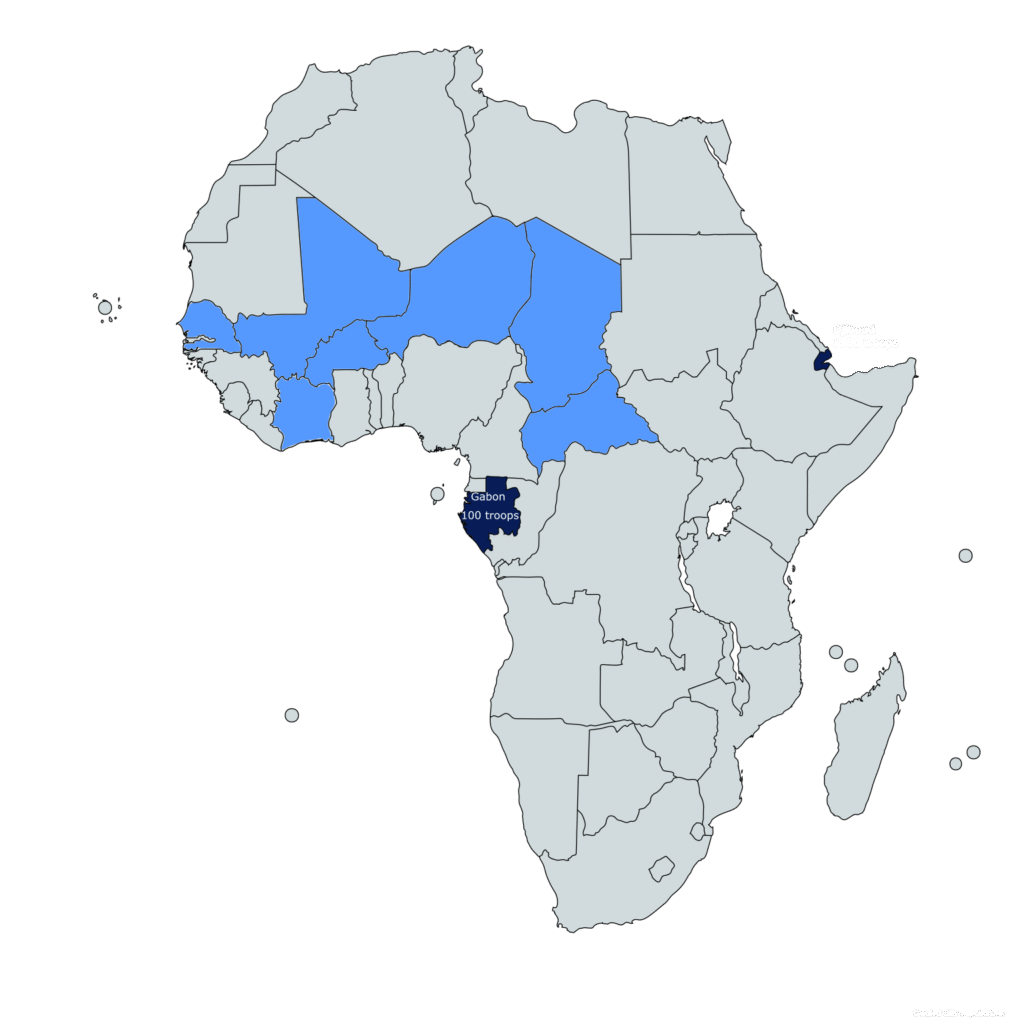

In dark blue are the two countries which will have remaining French troops after the end of 2025, in lighter blue are the countries France has withdrawn from in the period 2021-2025.

Outside of the AES, Russian forces are only active in the Central African Republic among the former French colonies. The difference between the Central African Republic and the countries in the Sahel is that there was no Central African coup that led to the changed allegiance. The government that expelled the French and invited the Russians is, ostensibly, the same government that the French had been backing militarily since 2013.

Wagner forces in Mali (Grey Zone mercenary community on Telegram)

The new coup government in Gabon remains the last country in West or Central Africa that will still maintain a French presence after the end of 2025. The overall picture of French presence in Africa shows that only half of the countries France has been expelled from since 2020 have suffered coups, which shows that there is a wider political frustration with French involvement from both military and civilian leadership in the region.

The French withdrawals being only a result of coup leaders wanting to avoid international criticism was a tempting explanation up until French forces started being expelled from countries still under civilian rule. There appears to be a trend of skepticism in the former French colonies against their former rulers, and the underlying reasons remain to be fully explained.

An attempted explanation

The rhetoric from African governments surrounding the pullouts cluster around two points, the first being that the French intervention is no longer needed, and the second being that removing French military presence means regaining sovereignty. At the same time, French leadership has continually claimed that the pullouts have been a voluntary process of “restructuring” their efforts, or that the military footprint will be replaced by a greater effort in developmental aid.

While it is true that the French had taken a mostly passive stance near the end of the Barkhane operation, it’s hard to argue that their contributions were a negative. In fact, the French leaving has left a security gap that has allowed Jihadist forces to increase their activity and held territory in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. In the coastal states that are not actively threatened by Jihadist activity, on the other hand, the effect of the removed French support is as of now not felt.

A single “benefit” comes from expelling the French, that being reduced international oversight. Reports of torture and massacres carried out by the governments’ armies and their allied militias are coming out of the Sahel, which can be carried out without international knowledge or condemnation if no one is there to report on it. For a military government, being able to carry out atrocities with impunity is a positive. Strengthening this argument is the fact that Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso have all expelled their local UN officials, due to annoying complaints about human rights abuses.

Captain Ibrahim Traore of Burkina Faso, who has become something of a symbol for anti-French and pan-African sentiment in the Sahel. (Ibrahim Traore on Twitter)

The French have not only supposedly worn out their military usefulness in West Africa, they’ve also worn out the patience of the local populations and governments there. The coup leaders, particularly Burkina Faso’s president Ibrahim Traore, have largely justified their takeovers of power with, among other things, pan-Africanist and anti-colonial talking points. Removing the need for French support removes leverage that a European power has on their government, and is therefore framed as a way to win back sovereignty by Sahel’s military rulers.

A country which very clearly demonstrates that these anti-French sentiments also exists among the common people of the region is Senegal. The 2024 Senegalese election cycle saw the ruling liberal coalition lose both the parliament and presidency to the pan-Africanist and anti-French PASTEF party. No coup was needed to move Senegal away from France.

A map summarizing the 2020s so far in the former French colonies. While coups can explain some of the changes, most of the withdrawals have happened in countries still led by their old regime.

Developments in nearby countries seem to have caused the previously Francophile government of the Ivory Coast to switch positions. The president and ruling party are still the same, but they are preparing for a presidential and parliamentary elections occurring later this year, in October and December respectively. Asking the French to leave, with the friendliest of rhetoric from any country that has done so, is a way to prevent the issue of cooperation with France to become an issue this election cycle like it did in Senegal.

With the general hostility towards France in West Africa, the French claim that they are leaving on their own terms comes off as a way to save face through a strategic setback. That said, the pullouts aren’t entirely negative for France. Operation Barkhane in the Sahel had cost up to €1 billion per year, and throughout its duration had taken the lives of 53 French soldiers. With no victory in sight, and pressing issues in Europe causing France to switch focus, the end of operation Barkhane was no tragedy for France. Leaving the war in the Sahel behind allows France to save costs and controversy.

Of course, if the French goal in the Sahel was to save costs and controversy, they never would have intervened back in 2013. France leaving behind a Sahel with weak and hostile states and growing jihadist movements is by no means a victory, but France wasn’t winning the war in 2021 either. Considering the French war goals from 2013, which were to destroy Jihadism in the Sahel and maintain the stability of the local Francophile states, it’s a war France lost.

Françafrique and the future

As French forces only remain in Gabon and Djibouti on the African continent, the future of the Françafrique is more uncertain than ever. It is clear that French influence in Africa has suffered a setback, the question is whether this setback is temporary, permanent, or the beginning of the end. A complete French loss of influence, or the end of the Françafrique, is not yet a sure fact.

For French influence to return to former heights, it would require two developments. For one, the West African states currently threatened need to withstand their current struggles against Jihadist groups, as France is unlikely to cooperate willingly with militant Islamist countries, and vice versa. The other requirement is that the elites of countries in the region again look towards France for support. This does not require democratization, as shown by the democratic and French-skeptic Senegal, and the dictatorial and traditionally Francophile Chad.

A major aspect of French influence is maintained through the CFA Franc still being the currency of 14 countries, including all of those that have recently broken off military cooperation with France. Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso have suggested a new currency to break off further with France, but no practical steps have been taken yet. As long as the CFA Franc states keep using the Franc they will be bound to the monetary policy of the French central bank, which gives France leverage and makes a full break less likely.

What makes a full and wide break with France more likely is that every rising tendency in Western and Central Africa is negative towards French influence. The winner of the war in the Sahel will be hostile to France, whether that winner is the alliance of junta regimes or an alliance of Jihadist movements. In democratic systems, hostility to France is most active among youth populist movements, leaving little promise for France with the next generation turning the trend away from French influence around.

If a full destruction of French influence in Africa is coming, it may come very quickly. We have already seen a cascade of military coups in the Sahel and the beginning of an electoral cascade on the West African coast. The CFA Franc is still in use and multiple leaders are still from the old Francophile elite, but those leaders and that currency are under pressure. With France unpopular and militarily absent, the remaining Francophile leaders are more likely to fold to military and political pressure.

Finishing thoughts

In an ideal world, the memory of the Françafrique would fade as the countries that used to depend on France gain the strength and wealth to stand without French support. French interventionism in Africa has always been self-serving, and the better future for the former French colonies would be that they solved the problems that caused their regimes to invite French support.

The development that we see today is that French support is rejected and French influence expelled, but none of the problems that caused the reliance on France are solved, and the new brand of anti-French pan-African leader has yet to prove that they can solve these problems into the future. In the best case, West Africa will stabilize, democratize and grow, without needing a great power patron, French or otherwise. In the worst case, the region’s potential is squandered, and Jihadists win the war in the Sahel.

If France is to maintain or rebuild its influence in Africa, there are two possible paths. One is to start overthrowing governments and make it impossible not to cooperate with France, which would be a break with what France has been doing, at least this century. The other path is for France to make cooperation with them more attractive. Of course, France does not need to maintain or rebuild its influence in Africa, and it may be best for all if they do not try.

Leave a Reply