The war in Sudan has entered into its third year, and shows no signs of a speedy conclusion. On the one year anniversary of the war’s beginning I posted an article here about the war up until that point, and the political background for the fighting.[1] If you have not read it and do not feel you know the basics of the war, check it out!

If you haven’t read the last article, or need a refresher, here are the two names and two acronyms you need to remember. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan is the leader of the Sudanese government, and leader of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). They are bad guys. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, usually known as Hemedti, is the leader of the government paramilitary turned rebel group Rapid Support Forces (RSF). They are worse guys.

Pictured are two good friends and allies, shortly before burning their country down in a war of ego. Hemedti on the left, Burhan on the right. Photo from AFP.

My main bias in reading and writing about the war is that I am opposed to the RSF. Hemedti is not just the aggressor in this conflict, his RSF is also clearly the worst side in the war. While both sides are guilty of crimes against humanity, the RSF is the most brutal in their atrocities, and with likely genocidal intent.[2] There is also a clear pattern of the RSF using rape as a tool of war and genocide, with their forces consistently being named as the perpetrator in interviews with rape survivors.[3] When the RSF loses ground, that should be seen as a good thing.

This article will consist of three sections. The first is the background of why Sudan matters and how the first year of war was. The second is a tactical overview of won and lost battles in the war throughout the past year. The third is an explanation of why the war is going the way it is going.

Why Sudan matters

The war in Sudan is in some respects the largest ongoing war in the world right now, and it has caused the world’s greatest ongoing humanitarian crisis. A minimum proven death toll collected by ACLED was 28,700 as of November last year, with the true death toll being far higher.[4] A less certain estimate puts the death toll at 61 000, of which 26 000 from direct violence, in Khartoum alone, where around 10% of the population lived pre-war.[5] The true scale of the war is not entirely known, as neither warring party wants the world to know the extent of the violence, but the war in Sudan might very well be the deadliest ongoing war in the world.

The war has launched the already fragile country of Sudan deep into crisis. Out of a population of around 50 million in 2023, 18 million people were already affected by food insecurity after a year of armed conflict.[6] By the end of the second year, that figure has risen to 24.6 million, almost half of the population.[7] Similarly, the number of displaced people has risen from 8.5 million people[8] to 12.7 million, of which 3.8 million have fled to largely fragile neighboring states.[9] The humanitarian situation in Sudan is worsening, and will keep worsening if the war does not reach a conclusion.

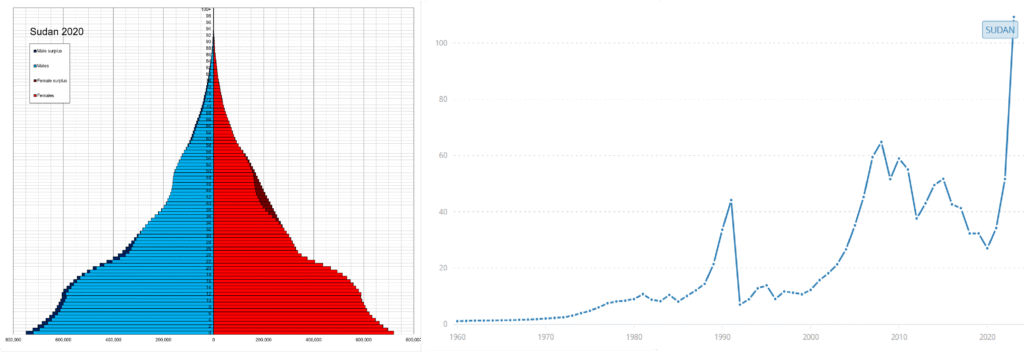

From a political point of view, Sudan is a country that holds great potential. Sudan had a population of around 50 million people prior to the war, with a growth so fast that around half of the population are children. According to world bank estimates the GDP of Sudan rose by over 100% from 2022 to 2023, the year the war started.[10] How Sudan ends up after the war is over is going to affect the region around it, whether Sudan is revitalized, weakened or slides into complete collapse. Most of Sudan’s neighbors are either weak, war-torn or both. Where Sudan ends up will inevitably be important for the development of East Africa as a whole.

Sudan’s somewhat bizarre population pyramid

Sudan’s similarly bizarre economic growth, according to the world bank

Considering the size of Sudan, the scale of the violence and the scale of the humanitarian crisis, general media disinterest in the war seems almost absurd.

Recap of the first year of war

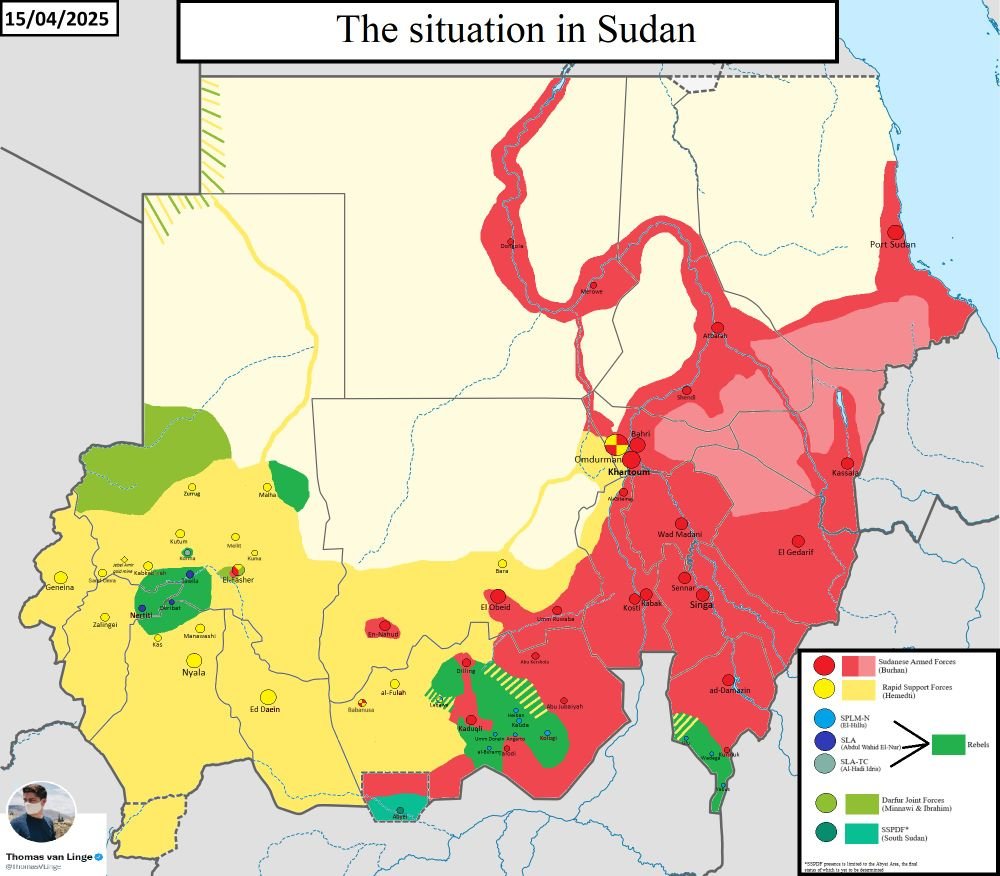

Burhan’s SAF has maintained its hold on the east of the country, including its most populated regions and the coast. Hemedti’s RSF has maintained a more tenuous hold on the west of the country, which is populated in part by the Arab Bedouin groups from which Hemedti himself comes from, and in part by the minority groups that Hemedti’s forces are persecuting. In the center of the country and the war lies the capital Khartoum, which was contested by the warring sides continuously for almost two years.

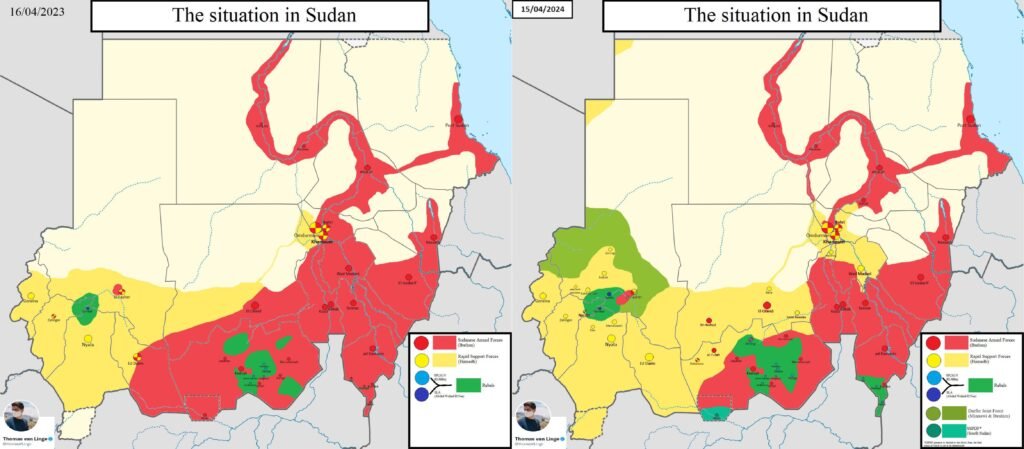

The war in Sudan on its second day (left) compared to its one year anniversary (right), with the RSF in yellow and the SAF in red. Of note are the RSF advances in the Gezira area. All war maps shown in this article are made by the excellent Thomas Van Linge.

Aside from the two main armies are a number of rebel groups, most of them formed during previous Sudanese civil wars. Most of these minor rebel groups have joined the side of the SAF, viewing them as the lesser of two evils. The old rebel movement from the time of South Sudan’s liberation, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), has split in two. One faction follows army chief Burhan’s deputy Malik Agar and supports the SAF, while the other, headed by Abdelaziz al-Hilu, supports the RSF.

Sources, first part:

[1] https://hugismen.no/one-year-of-war-in-sudan/

[2] https://www.globalr2p.org/publications/urgent-alert-on-the-risk-of-genocide-in-north-darfur-sudan/

[3] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/04/sudan-rapid-support-forces-horrific-and-widespread-use-of-sexual-violence-leaves-lives-in-tatters/

[4] https://acleddata.com/conflict-watchlist-2025/sudan/

[5] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/crln9lk51dro

[6] https://www.wfp.org/stories/one-year-sudans-war-its-people-yearn-peace-amid-soaring-hunger

[7] https://www.wfp.org/emergencies/sudan-emergency

[8] https://www.unhcr.org/news/briefing-notes/thousands-still-fleeing-sudan-daily-after-one-year-war

[9] https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/02/1160161

[10] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=SD

The tactical side of the war

In my previous article on Sudan I commented on the SAF making more gains as the war went on, but no side having a decisive edge. At the time of writing this article, a year later, one side has a very clear edge, that being the SAF. This was, however, not before the RSF had carried out a major offensive in central regions of the country and looked, at least for a few months, like they could win the war.

Map of Sudanese Wilayas, usually referred to in English as states, or in this article as provinces for clarity’s sake.

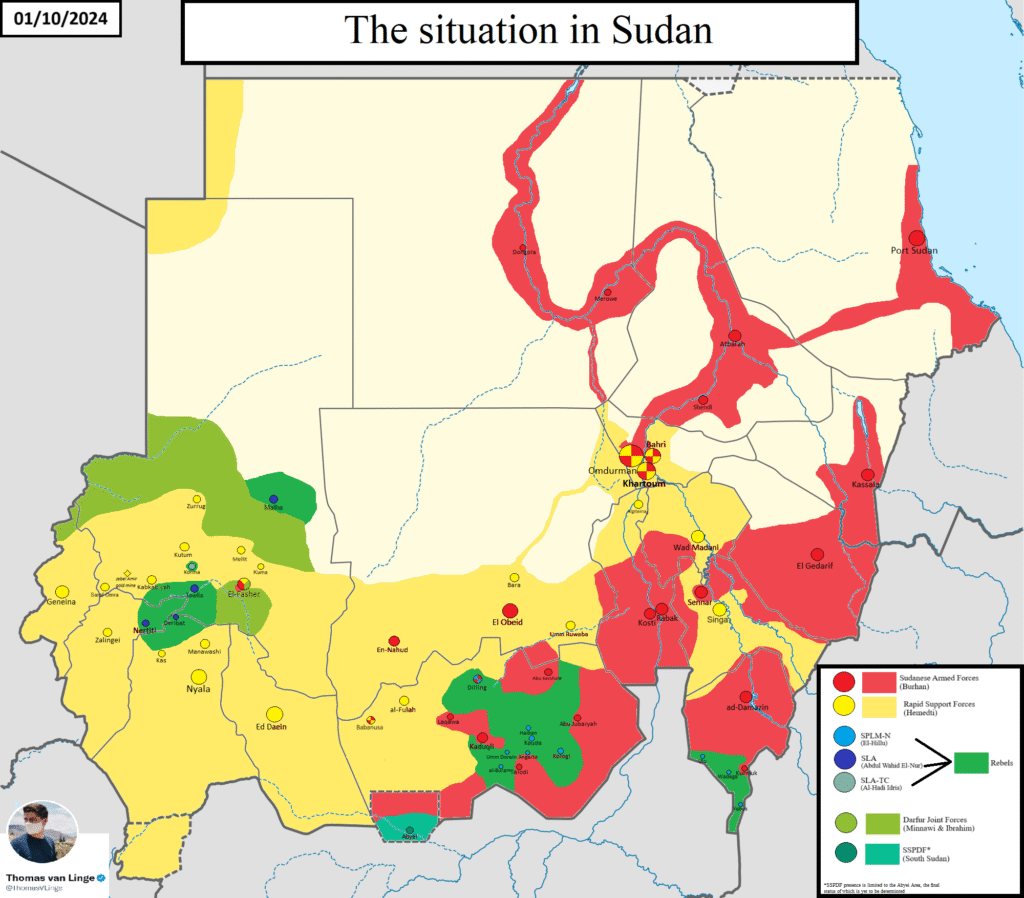

The overall picture of the war is that the RSF has lost the campaigns in Darfur and along the Nile, while still being on the offensive in Darfur. The campaign in Kordofan is still slow for both sides, and they are trading victories. In all, the situation for the RSF is grim, and their final defeat, while still some time off, seems increasingly likely. What follows is a more detailed description of each of the four campaigns from the last year.

Offensives along the Nile

In late June last year, RSF forces, already in control of most of Gezira province, moved south on a major offensive to capture Sennar. The collapse of the SAF defense of Sennar was rapid, and the provincial capital of Sinja was captured within a week.[1] The RSF continued consolidating control in Sennar province, and in August began incursions into the Blue Nile province. It was during this time that the territorial control of the RSF reached its zenith.

War map of Sudan with the RSF at their territorial peak.

All three provinces are part of what’s been called Sudan’s breadbasket, and the offensives there have disrupted Sudan’s food production, exacerbating the famine.[2] The incursions into the Blue Nile province have disrupted the food production and caused local food shortages without the RSF actually having captured much territory.[3]

After having occupied most of Sennar, the RSF soon began losing ground again. By November last year they lost control of Sinja, and in January they lost control of Wad Madani, the capital of Gezira province that they’d held for over a year.[4] The SAF carried this momentum into the still ongoing battle of Khartoum, and the campaign in Gezira and Sennar may signal the RSFs permanent loss of ability to bring the war to eastern Sudan.

Battle of Khartoum

In March this year, after almost two years of fighting, the SAF finally won the battle of Khartoum. The capital was where the war started, and control of it is significant due to the city’s central position, large population and political importance. Five million people live in Khartoum, and the city is located where the Blue and the White Nile rivers meet. Before the RSF coup attempt began, Khartoum was one of the few parts of Sudan that had not been directly affected by previous decades of civil war.

SAF troops cheering after the recapture of the presidential palace in Khartoum. Picture released by the SAF.

After a long stalemate and battle of attrition in Khartoum, the SAF began rapidly winning ground in early 2025. Khartoum Bahri was fully captured by the SAF in February, and Khartoum proper was captured in March. The only RSF forces that remain in the city hold on to the outskirts of Omdurman, but it will only be a matter of time before they are forced to either abandon the city or surrender. The battle for the city as a whole is over.

Campaign in Kordofan

The campaign in Kordofan has been a sideshow in the war effort of both sides. Territorial control in the region is split between the warring parties, and the war is mostly conducted by the RSF keeping key cities under siege, while the SAF awaits reinforcements. Over the new year the SAF has been increasingly launching counterattacks in the region, which may signal a reversal of momentum in the Kordofan campaign.

In June last year the RSF has captured the city of Al-Fulah, capital of West Kordofan province. The cities of Kadugli and Babanusa are still under siege, while the siege of El Obeid was lifted in February. Overall one city changed hands throughout an entire year of campaigning, very slow compared to the rapid attacks and counterattacks in the rest of the country.

Map of the war on its two years anniversary, with the RSF having lost most territory gained since the first day of the war.

With the RSF expelled from Khartoum and the Nile region, there is nothing stopping the SAF from advancing west into Kordofan, where the situation on the ground was already even. The next year will probably lead to major territorial losses for the RSF in the Kordofan region.

Campaign in Darfur

Darfur is the one region of the country where the RSF is still the one on the offensive. Darfur is the region where the RSF has their recruitment base, it is where they control the most territory, and it contains the border crossings with Chad where the RSF receives their weapons from the UAE. Four of five provinces of the Darfur region is under the complete control of the RSF, and the regional capital of Al-Fashir, the last stronghold of the SAF in the region, is under siege.

A devastated townscape in Al-Fashir. (Reuters)

Darfur is also where they carry out their genocide. People from non-Arab ethnic minorities are victims of massacres, mass rape and torture wherever the RSF is in control. The most recent “victory” of the RSF in Darfur was conquering the Zamzam refugee camp near Al-Fashir, which held around half a million refugees fleeing from RSF advances in the rest of Darfur.[5] Most of these people have fled into Al-Fashir proper, where the population of internally displaced people already matched the local population, around 200 thousand of each.[6]

Should the SAF forces in Al-Fashir be defeated, the entire population of almost a million, of which 700 thousand were already refugees, will be at the mercy of the RSF. With the RSF’s history of atrocity there is no telling what they will do.

Sources second part

[1] https://www.info-res.org/sudan-witness/reports/sudan-monthly-update-the-rsf-makes-strategic-gains-across-sennar-state-with-takeover-of-jebel-moya-and-sinja/

[2] https://peoplesdispatch.org/2024/11/04/rsf-is-depopulating-war-torn-sudans-breadbasket-amid-an-unprecedented-famine/

[3] https://atarnetwork.com/?p=8947

[4] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/1/11/sudan-army-says-its-forces-enter-wad-madani-in-push-to-retake-city-from-rsf

[5] https://www.msf.org/desperate-situation-people-fleeing-zamzam-camp-sudan

[6] https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/sudan/sudan-humanitarian-access-snapshot-al-fasher-and-zamzam-8-april-2025#

The strategic side of the war

The past year of rapid RSF advances followed by similarly rapid RSF collapses begs the question of why the RSF is now losing, when they were doing so well. I believe it boils down to three factors: the RSF has a narrower base of popular recruitment, the RSF has lost international support while the SAF is gaining, and the RSF faces more resistance from other rebel groups.

There is one x-factor in the war, which is the ongoing political crisis in South Sudan. If that spirals out of control it could bolster the odds of the RSF or increase the likelihood of a total state collapse in Sudan.

Recruitment

The RSF grew out of a collection of older Janjaweed militias, which were Arab militias recruited from the nomadic and semi-nomadic population in Darfur during the Darfur war in the early 2000s. This narrow recruitment base was convenient for the old president Bashir in the Darfur war, as it gave him soldiers with a direct stake to the territory, but the RSF is consequently an institution without tradition for broad recruitment in all of Sudan.

Janjaweed militants on camelback during the previous war in Darfur.

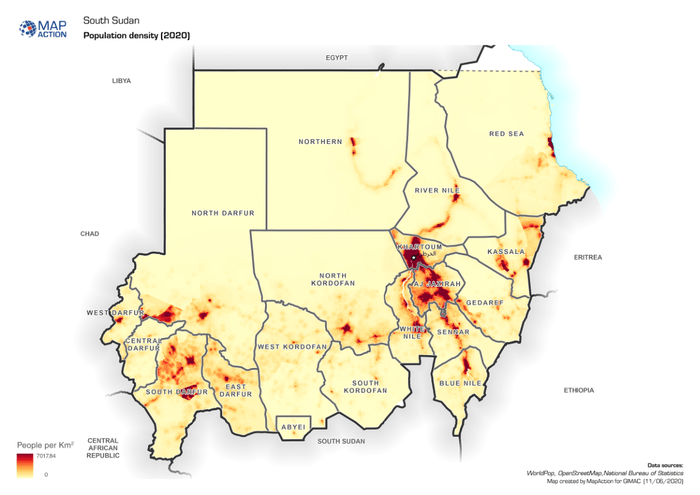

With the loss of all territory in the east of the country, the RSF controls regions that held less than 30% of the country’s population before the war. The regions the RSF does control are also ethnically mixed, populated both by the Arabs that the RSF recruits from and by minority groups that the RSF is actively persecuting, and therefore unlikely to lend much support to the RSFs war effort.

Population density map of Sudan by ReliefWeb. Aside from Darfur, every meaningfully populated region in Sudan is held by the SAF. The biggest city in North Kordofan is El-Obeid, which the RSF has failed to capture by siege.

On the other hand, the SAF controls most of the country, including Sudan’s most populated and most homogenous regions. In addition, every region that is this far unaffected by fighting is controlled by the SAF, the ones controlling government before the war. This means that the SAF, which has always been an army based on broad popular recruitment, probably has the ability to recruit and train multiple times the number of soldiers that the RSF has in the same time span.

In the beginning of the war this was not a big problem for the RSF. The initial balance of power was similar, with the SAF estimated to have 120 thousand troops compared to the RSF’s 75 thousand more experienced soldiers.[1] As the war dragged on and thousands of soldiers died on both sides, however, the two armies have had to resort to mass recruitment to keep the war going, a dynamic that heavily favors the SAF.

International support

In the beginning of the war, the RSF was the party with the most direct foreign support, despite the SAF having international recognition. Since then, the RSF has lost the support of one of their backers, while the SAF has received weapons shipments from an increasing number of foreign powers. Both parties are under arms embargoes by the US and EU, which backers of both sides are quick to ignore.

A network of states and non-state actors banded together to support the RSF at the beginning of the war. The United Arab Emirates sent weapons to the RSF, using the Russian Wagner group and Kalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army to smuggle heavy weapons into Sudan through Chad, the Central African Republic and Libya.[2] Since then, Russia has changed their policies to support the SAF instead.[3] The UAE remains the main backer of the RSF.

RSF soldiers inspecting a cargo plane from the UAE that they shot down thinking it was from the enemy. The weapons on board were indeed meant for the RSF, but were meant for the RSF to use. Screenshot from a video released by the RSF soldier on Twitter.

The SAF receives arms shipments from chiefly Russia, Iran and Turkey. Russia’s switch to support the SAF deprives the RSF of a backer, but it also aligns Russian policy with that of Iran, which was already selling drones to the SAF.[4] Turkey’s support also consists of the sale of drones, and has been carried out in secret, as it is in violation of the aforementioned arms embargoes imposed by their allies.[5] The new support for the SAF can be transported in through Port Sudan, which is cheaper, safer and more effective than the overland routes that the RSF is utilizing in western Sudan.

Rebel loyalties

In the earliest stages of the war, most former rebel groups in Sudan held off on joining the conflict, waiting to see which side gained a lead and which side could be reasoned with.

In Darfur, most if not all of the old rebel groups from the Darfur war have taken up arms to again fight the RSF.[6] Many of these groups have begun cooperation with the SAF, and these groups have been crucial in delaying the RSF victory in Al-Fashir, for example. Farther south, the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) has been disrupting RSF rule over the four southern Darfur provinces, and preventing the RSF from having a true consolidated base of power.[7]

Farther east, in Khartoum and its surrounding regions, popular militia movements have formed, many originating in the democracy movement.[8] Their reasoning is the same as the reasoning of the people of Darfur. The actions of the RSF make cooperation with the SAF, which has been an eternal enemy of Sudanese democratization, seem worthwhile. By carrying out atrocities the RSF creates its own opposition on the advance.

The only former rebel faction of note to join the RSF’s cause is Al-Hilu’s faction of the SPLM. They fight the SAF in Kordofan together with the RSF, after having previously fought both sides in the region. In March they decided to form a parallel government together with the RSF, which may be the beginning of a preparation to attempt RSF-led independence in Darfur and Kordofan if the war as a whole cannot be won.[9]

South Sudan

In 2011, South Sudan won its independence from Sudan, and it was ruled by revolutionary leaders from the civil war. In the presidency was Salva Kiir, and as vice president was Riek Machar. A power struggle between them would lead into a civil war, after Salva Kiir dismissed Riek Machar from government.[10] In 2020 the war was ended by peace agreement, and Riek Machar was sworn in as vice president under president Salva Kiir.[11]

Pictured are two good friends and allies, Riek Machar (left) and Salva Kiir (right) shortly after having burned their country down in a war of ego. Photo by UN.

On March 26th, 2025, Riek Machar was detained by security forces loyal to Salva Kiir.[12] The arrest follows clashes in Nasir between government forces and the previously oppositional Nuer White Army, and the subsequent deployment of Ugandan special forces in the capital to support Kiir’s grip on power.[13] At the time of writing, the outbreak of a true civil war is still not certain, as the rest of the old opposition has yet to mobilize.

If the crisis in South Sudan turns into a full-scale civil war, it may merge with the war to its north. Depending on where the battle lines are drawn and how cross-border allegiances develop, this serves as an x-factor that leaves the final conclusion of the war in Sudan as more uncertain. Of course, the conclusion for any war in South Sudan is known, which is Riek Machar again being sworn in as vice president under Salva Kiir.

Outroduction

The war in Sudan is still not a source of much optimism, and it seems overwhelmingly likely that I will have to write another article about the still ongoing struggles in the country in a years time. Even if the RSF is knocked out of the war, it is unlikely that true peace will come to Sudan in a year.

The one optimistic takeaway is that the worst possible victors of the war, the RSF, don’t seem to be doing well. Time will tell if the SAF’s advantages will translate into a wipeout of the RSF, if the RSF can hold their positions in the west or if the RSF can rebound and recover.

If you are left wondering what a global audience can do about brutal warlords in a faraway land, as I often find myself, there is actually something that makes a real difference. Even in the areas where global aid organizations can access, the funding that they receive is not enough to make up for the magnitude of the crisis. If you donate to https://www.wfp.org/support-us or https://www.msf.org/donate or any other good charity of your choosing, it really doesn’t cost much to save a life.

Sources third part

[1] https://theconversation.com/sudan-is-awash-with-weapons-how-the-two-forces-compare-and-what-that-means-for-the-war-205434

[2] https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/libya-sudan-haftar-rsf-supply-lines

[3] https://jamestown.org/program/russia-switches-sides-in-sudan-war/

[4] https://adf-magazine.com/2025/02/iran-russia-seek-military-bases-in-sudan-as-civil-war-rages/

[5] https://stockholmcf.org/turkeys-baykar-sent-120-mln-in-drones-and-missiles-to-sudanese-army-report/

[6] https://sudantribune.com/article279446/

[7] https://sudantribune.com/article279993/

[8] https://www.dabangasudan.org/en/all-news/article/sudan-revolutionaries-join-army-ranks-to-expel-rsf-from-khartoum

[9] https://sudantribune.com/article300100/

[10] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2013/12/16/heavy-gunfire-rocks-south-sudan-capital/

[11] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/2/22/south-sudans-rival-leaders-form-coalition-government

[12] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0q1jppzp4no

[13] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/3/11/uganda-deploys-troops-in-south-sudan-as-civil-war-fears-grow

Leave a Reply